If you want to get engagement on Twitter right now, posting some scary chart about fertility is a fool-proof method. James Pethokoukis did this to perfection last week:

The natural conclusion to a chart like this is that paying people to have kids doesn’t work, and it especially doesn’t work in South Korea with its downright draconian work culture and high levels of conformity. Basically, it’s a cultural issue, and unless pronatalism once again has its time in the sun, South Korea is doomed to a slow extinction.

The idea that culture is the culprit for the developed world’s cratering birth rate is a popular one that is only growing in consensus. Singapore’s former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew probably summarized the idea best when he wrote:

I am convinced that even super-size monetary inducements would only have a marginal effect on fertility rates. But I would still go ahead and offer the bonus, for at least a year, just to prove beyond any doubt that our low birth rates have nothing to do with economic or financial factors, such as high cost of living or lack of government help for parents.

They are instead the result of changed lifestyles and mindsets. … Once women are educated and have equal job opportunities, they no longer see their primary role as bearing children or taking care of the household. They want to be able to pursue their careers fully just as men have always been able to. They have very different expectations about whether or whom they should marry because they are financially independent. There is no turning back the clock, unless we want to stop educating women.It’s not hard to find evidence for his argument. On an anecdotal level, as a 25-year-old dude, I very rarely meet a woman who wants to have kids. Obviously my experiences mean very little in the grand scheme of things, but I’d bet many of you have experienced something similar, and polls consistently back this up:

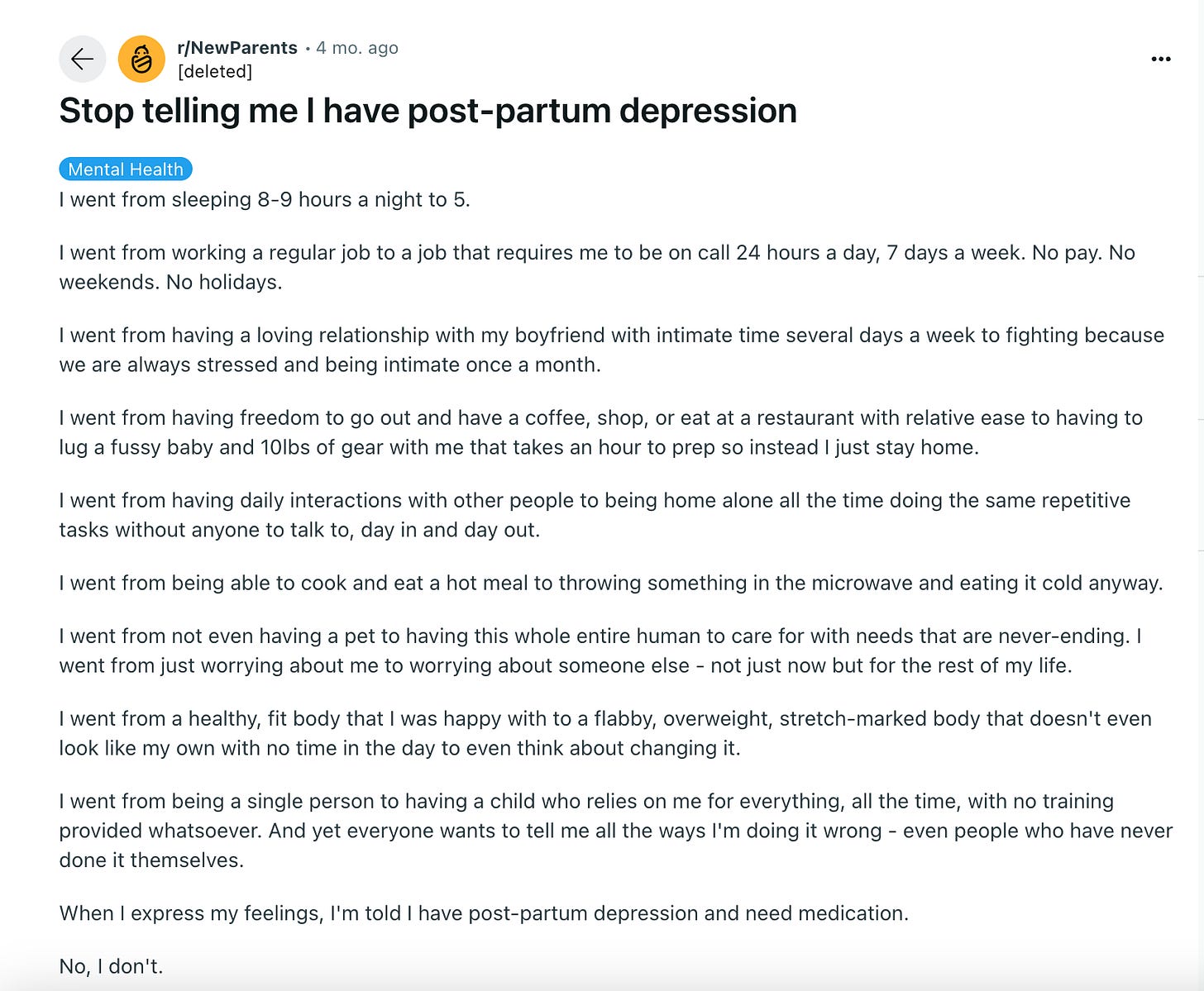

On a micro level, it’s a lot easier to find content that makes having kids sound like hell than it is to find content that makes having kids sound somewhat enjoyable. A quick search of “parents” in Reddit shows subreddits like “childfree” (1.5M subscribers), “entitledparents” (2M subscribers), and “regretfulparents” (126K subscribers). As you’d then expect, it’s much easier to find stories like this:

or this:

or this:

then it is to find stories like this:

Meanwhile, over at TikTok, which ~20 million women aged 18-30 use religiously, an account that makes objectively hilarious videos on why women shouldn’t have kids has 512,000 followers and 14.5M likes, and videos like this go viral pretty frequently:

And, seemingly most damning, on a macro level, there are a bunch of countries that have tried throwing money at the fertility problem, and for the most part, they have not worked particularly well. The result is that many smart people now believe that “paying people to have kids doesn’t really work”.

But, although I agree that changing the culture is crucial, I don’t believe that writing off financial solutions is the right conclusion. Instead, I believe that these countries are not spending nearly enough money on boosting fertility.

We Really Aren’t Spending That Much On Fertility

If South Korea has spent $270B since 2006 on fertility incentives, that means they are spending $15B a year. That would be one of the cheapest items on their budget, far below education, R&D, agriculture, and “social order, safety”.

Japan, another country that is slowly turning to dust, wants to spend about $25B annually on babymaking incentives. That is only 3.36% of the $744B budget, far less than the 33% allocated to social security.

Poland spends about 40 billion zlotys a year on babymaking incentives1, only ~4.6% of it’s 866 billion zlotys budget. They spend about 20% of the budget on “social protection benefits”, which is a fancy word for social security.

The US’s babymaking incentives pretty much boil down to the child tax credit, which gives $2,000 in tax credit for each kid under 17. Assuming that everyone of the 73 millions kids under 17 are claimed, that is $146B in “spending” each year. That is only 2.4% of the $6.1T budget, of which 21% went to social security.

I could keep going, but you get the point. We just aren’t spending all that much on fertility incentives, and definitely not compared to things like social security.

Fertility Incentives Actually Work Pretty Well

The question then becomes: is it worth spending more on fertility incentives? The evidence seems to point to the answer being yes.

A review of the literature finds that “regular cash transfers have small but positive effects on period fertility”:

Azmat and González (2010) estimated that an introduction of the additional tax credit for working mothers with children below age 3 and an increase in tax deductions for families in Spain led to an increase in a birth probability by 3 births per thousand women.

In Hungary, a 1 percent increase in child-related benefits was assessed to increase period total fertility by 0.2% (Gábos et al. 2009).

In their study on 18 OECD countries, Luci-Greulich and Thévenon (2013) estimated that an increase in the expenditures on cash benefits as a share of GDP per capita by 1 percentage point would lead to an increase in the tempo-adjusted TFR by 0.02.

The Allowance for Newborn Children (ANC) introduced in Quebec (Canada) in 1988 offered a one-time payment of C$500 (over 400 US Dollars at that time) at first and second birth and 8 quarterly payments of C$375 for the third and higher order births. These amounts were increased in subsequent years and in 1997, when the program was terminated, parents received C$500 after the first birth, C$1000 in total (paid in two installments) after the second birth and C$8000 in total (paid in 20 quarterly installments) for the third and higher order birth. Milligan (2005) estimated that period fertility increased by 12% overall and the third or higher fertility by 25%.

In 2004 Australia began offering a one-off payment of A$ 3,000 (around US $ 2,200 at that time), increased to A$ 4,000 in 2006 and A$ 5,000 in 2008. Drago et al. (2011) estimated the baby bonus had a small significant effect on both birth intentions and birth rates, increasing the birth rate by about 3.2%.

The North-Eastern Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia in years 2000-03 introduced a baby bonus of EUR 3,000 for second births and EUR 4,600 for third and higher order births (Boccuzzo et al. 2008). The bonus was paid only to women whose income was below a certain income threshold. The number of births in this period increased by 2-3%, likely because of a decline in the abortion rate.

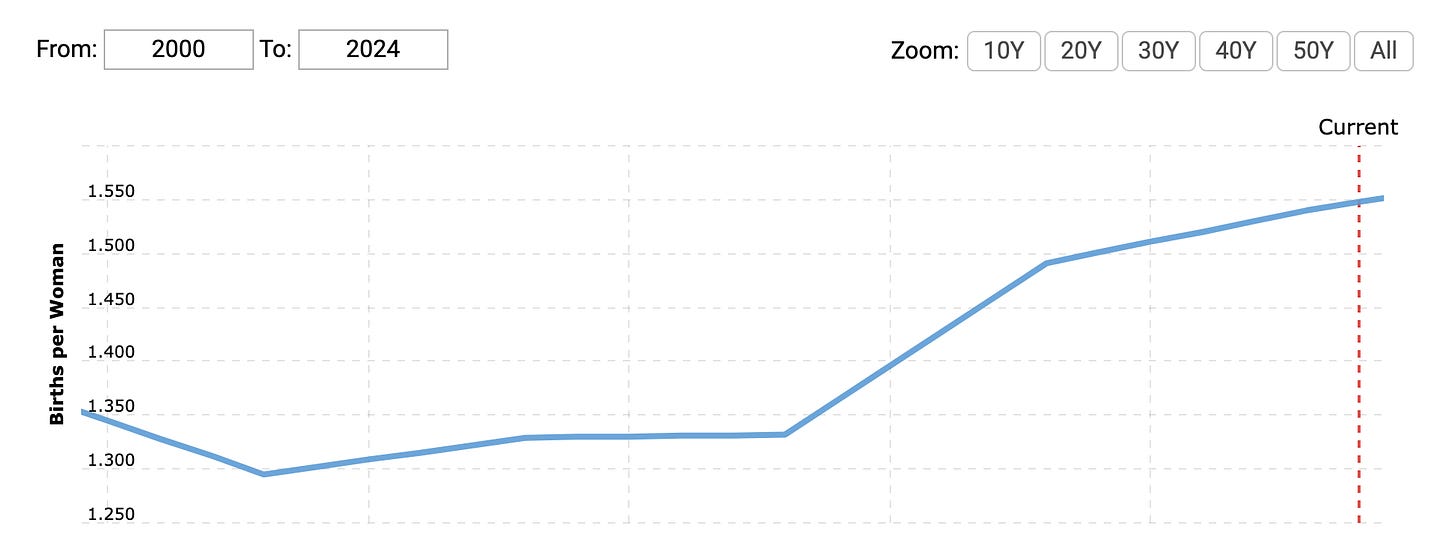

For a current real-world example, in 2015 Hungary began spending about 5% of its GDP on babymaking incentives, including a lifetime tax exemption for women with four or more kids, a baby grant roughly equal to 5 years minimum wage, and highly subsidized mortgages. The result is a fertility rate that looks like this:

People shit on them for not bringing fertility back to replacement level (2.1), but unless I’m really missing something here, this doesn’t look like a failure. It looks like a policy worth doubling down on.

That’s what I believe every country with a fertility problem (so…basically every country) should do.

How Much Should We Spend?

In the US, it costs about $331,933 to raise a child to 18. That means the average child costs about $18,440 each year to raise. I propose that we give each parent that amount per kid each year.

In other words, completely subsidize parenting.

Assuming that there’s about 73M kids under 18 in the US, a program like this would currently cost about $1.35T each year.

How The Hell Are We Going To Afford That?

$1.35T is a big number, but it just so happens that we spend about $1.3T each year on social security. So, all you have to do to fund this program is cut social security. Yes, it’s a little bit more expensive, but it’s worth it when you consider all the benefits from funding young people instead of old people.

Basically, I’m proposing this.

The people who receive social security are retirees, aka the least productive portion of society. The money you pay them, you never see back. Young people, by contrast, are the most productive portion of society, just by virtue of having the most years left in the workforce. Unless you end up homeless or suffer an early death, the odds are strong that you will return far more than $332K in economic value. This makes subsidizing parenting a far more prosperous endeavor than funding retirement.

Now, before you call me a heartless bastard who doesn’t care about old people, consider this:

Social security is doomed unless you can increase the youth population.

People 65 and up are already the richest demographic by far, which makes sense considering that they’ve had their whole lives to accumulate wealth. Social security is basically equivalent to taking money from the poor and giving it to the rich.

If you fund parenting, then you are removing a big expense in people’s lives. Without this cost, it’s likely that even the lowest earners won’t “need” social security to retire.

So, by swapping out social security for the cost of parenting, you are replacing an ineffective and unnecessary program that does nothing to improve the economic wellbeing of the country with one that incentivizes the creation of our most crucial and productive members.

That seems like a good deal to me.

A Piece Of The Pie, Not The Whole Pie

In 2015, Hungary started spending 5% of their national GDP on fertility incentives. Their birth rate at the time was 1.44. It is now 1.59 and climbing. That’s a 10.4% increase. My plan spends $1.35T a year, which is about 5% of the US’s national GDP. Assuming that it has the same effects in the US as it did in Hungary, our fertility rate would increase from 1.66 to 1.83 over the next 9 years.

That’s already a good start, but I think the effects would be even better than that considering that Hungary’s birth rate has increased by 27.2% since the current regime took over in 2010 and that direct cash is more persuasive than tax benefits. If we can speed run that 27.2% increase we’d be right at a 2.11 fertility rate, also known as replacement level.

That’s an amazing result, but even if it happens, I still believe it’s just part of the solution to our fertility woes, not the solution. In that way, it’s basically analogous to the sulfur dioxide “solution” to climate change.

You still need to fix the culture. As this astute commenter notes:

We need a lot of cute babies. We need to get boost our marriage rates and encourage people to get started earlier. We need to kill the idea that you shouldn’t have kids because of the environment, or that kids will ruin your career. We need Taylor Swift to write songs about how dope being a mom is. We need to stop shitting on women who want to be stay at home mothers. Basically, we need to make having kids cool again.

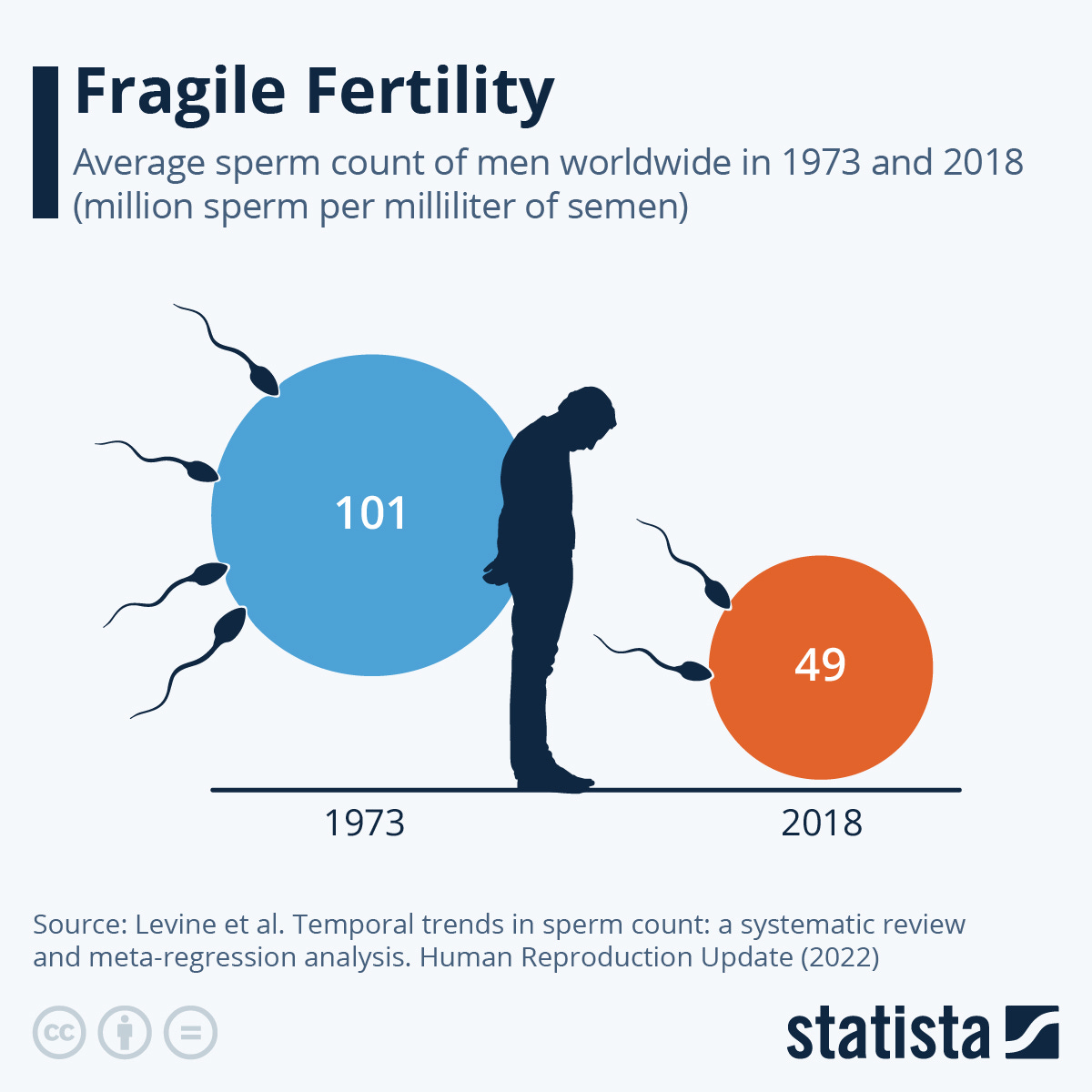

You also still need to address our biological issues. It’s going to be hard to fix the fertility crisis if 17.5% (and rising) of the global population experiences infertility issues. Graphics like this should terrify you:

We need to eat healthier. Work out more. Sleep better. Get some sun. Cut down on our microplastic exposure. And then we need to use biotech to it’s maximum potential. IVF. Frozen eggs. Artificial wombs. We have to all become fertility e/acc’ers.

Ultimately, fertility is such a tricky issue because it’s all-encompassing. If people feel like it’s too expensive, they won’t have kids. If people think having kids are a terrible pain in the ass, they won’t have kids. If people are literally unable to have them, then they obviously won’t. The only way to solve this issue is by attacking it from all angles.

A fertility incentive policy like this can be a great stopgap until we fix the cultural and biological root causes.